Coffee is a hot trend. The black liquid is consumed, loved and celebrated at any time of day – in speciality cafes and at home. And there’s a real passion now for coffee making that appreciates craftsmanship and exquisite flavour experiences.

More and more coffee shops are popping up like mushrooms. Many of them look like creative workshops and the aromas are amazing. Here the focus is on just one object – properly prepared coffee. Gone are the days when no-one cared where the coffee came from or when things such as maple syrup, milk fat content or cinnamon took centre stage. Flavour authenticity is the guiding principle – and is rapidly gaining ground. It is encouraging new connoisseurship in terms of coffee making and pleasure.

The flavour begins with the bean, which is grown in the equatorial regions of the world. Whereas African coffee tends to have a rather fruity flavour, coffee from Brazil delivers more chocolatey notes. The most popular coffee varieties are Arabica and Robusta. Robusta accounts for around 30% of world production and is grown in places such as Brazil and West Africa at altitudes between 300 and 800 metres above sea level. The higher-quality Arabica makes up approximately 70% of global production and comes from East Africa, Latin America, India and Papua New Guinea. Because this “highland coffee” is grown at altitudes between 600 and 1200 metres above sea level, the growth of the coffee plant is slower and it is therefore able to develop more aromatics. Then there is the extremely expensive Kopi Luwak coffee which goes through an extremely unusual process. The fruit of the coffee cherries is eaten by wild civets in Indonesia, which subsequently defecate the bean whole. The beans are then used to make this coffee with its characteristically rich and earthy aroma.

The flavour is also determined by the roasting process. The beans are roasted for 5 to 13 minutes for coffee, and up to 20 minutes for espresso. The longer roasting reduces the acid content and therefore sensitive stomachs are better able to tolerate espresso. Roasting demands the expertise of a master roaster who is able to differentiate between numerous shades of colour. Too light may mean that the coffee is sour, too dark could mean too bitter. An exception here is green coffee, which has recently become increasingly popular and comes from various equatorial countries, including Peru. The beans are not roasted after drying, so they have a high anti-oxidant chlorogenic acid content. There is lively on-going debate as to whether this acid has a weight-reducing effect.

Lots of beans, lots of flavours. You can now enjoy the diversity of the beverage in specialist cafes such as Berlin’s “Bonanza Coffee Heroes”. These places celebrate the art of coffee making. The focus is on quality and a passion for the product throughout every stage of the process – from responsible bean purchasing and (often in-house) roasting through to the right fineness of grind, proper preparation and serving.

from Stelton

2 Brewer stand set from Kinto

3 Drip set from Hured

4 Dripper from Zero Japan

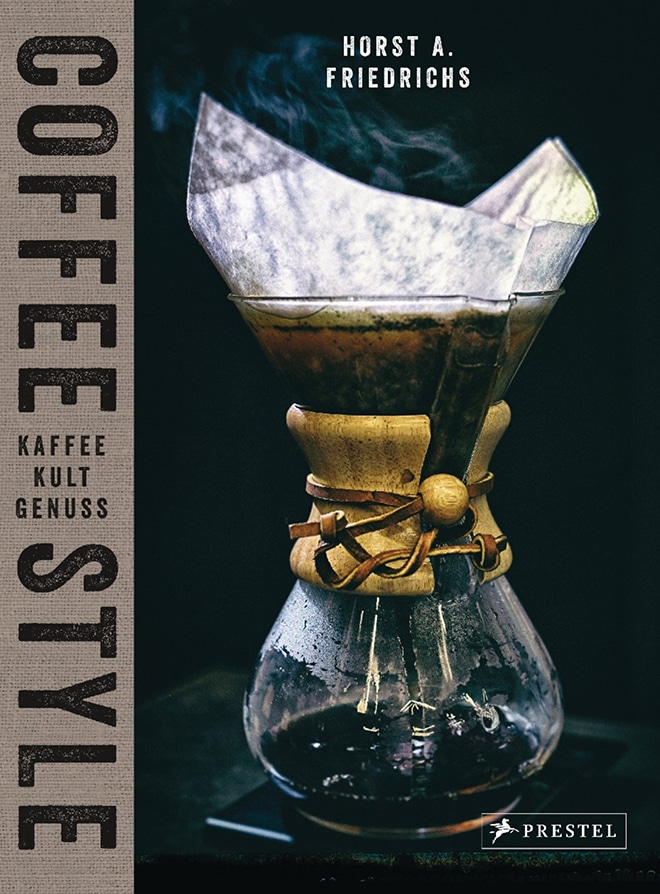

Photographer Horst Friedrichs has investigated the scene across the globe and portrayed it in his illustrated book entitled ‘Coffee Style’, which was recently published by Prestel. “The development started off in California and in the beginning it was a subculture phenomenon,” says Friedrichs. “However, the trend has continued to spread in the same way as wine and tea and is becoming a lifestyle thing.” His photos clearly show the fascinating alliance that often exists between coffee connoisseurship and style consciousness. Environmentally responsible cultivation, fair trade and sustainability are all writ large by the new coffee masters. For instance, Intelligentsia Coffee from Chicago displays all coffee varieties on its website with production region, flavour, harvest time and name of the coffee grower. The story of the product is also often told in blogs or on the packaging.

The new specialty coffee movement is known as the “Third Wave”. In the First Wave, coffee became a mass consumer product thanks to manufacturers such as Jacobs. The Second Wave was initiated by Starbucks, which for the first time concentrated on single-origin coffees from a single variety of bean in contrast to lower-quality blends. It also offered its famous customisation options. The Third Wave is characterised by sustainability as well as a passion for aesthetics and “craft” products that are well-made and down-to-earth. Connoisseurship, precision and attention to detail are required. Handmade products give a sensual experience that has a new appeal in our age of digitisation.

Yuppiechef Blog

Manual coffee making is also ideal for the home environment. It isn’t time-consuming and the process allows maximum control over preparation and flavour intensity. However, in order to brew a really good coffee, a few things need to be borne in mind – starting with the grinding of the beans. Consumers who buy ready-ground coffee lose out on a certain refinement of flavour. It is far better to grind the required amount of beans just before use. The range of coffee grinders – from classics to handy modern travel grinders – offer the perfect machine for any requirement. Simply put the right amount of beans into the grinder (approx. 15 to 17 grams per cup), turn or crank the handle and that’s it. The aroma, too, is to die for!

2 Coffee grinder from Zassenhaus

3 Coffee maker from Kitchen Craft

4 Coffee maker and kettle from Bialetti

There are essentially two ways of infusing ground coffee, either with a filter or with a French press. The former is referred to as “Pour-Over Coffee”. Here you need a filter or filter insert, filter paper and a beaker, cup or pot into which to pour the coffee. The filter – also known as a “dripper” – may be made of glass, plastic, stainless steel or porcelain and its inside can be smooth, ribbed or spiral-shaped with a small or large opening. Rinse the filter paper first of all with hot water to remove small paper particles and neutralise the flavour. Fill the filter with freshly ground coffee. Bring the water to the boil and leave it to stand for 30 to 60 seconds so that the temperature cools down to about 95 degrees, which allows the aromas to develop better. Then pour the coffee slowly with a circular motion.

With the French press (also known as a cafetière, plunge pot or coffee press), loose ground coffee is spooned into a glass pot, slightly cooled boiling water is poured over it and the contents of the pot are stirred once. The plunger is then placed into the pot and the coffee infuses for 4 minutes in the pot. The plunger is then fully pressed down so that the coffee is forced to the bottom of the pot. If you don’t pour out the entire contents immediately, bear in mind that the coffee remaining in the pot will continue to infuse and become stronger.

And finally, there’s the AeroPress, which offers a mix of the pour-over and French press processes. The method you choose also determines the fineness of grind of the coffee. For the pour-over method you need medium or coarse ground coffee, but not as coarse as for the French press where it should be about the same coarseness as sea salt. The basic rule of thumb is: the longer the contact the ground coffee has with the water, the coarser the grind.

The opportunity for creative expression increases the enjoyment of coffee. This is particularly reflected in the growing popularity of coffee-related courses. There are courses where participants learn how to evaluate the coffee aroma and flavour profile in a coffee tasting technique known as “cupping”. Other courses offer the chance to gain a barista certificate and create perfect “latte art”. Amateur coffee connoisseurs are increasingly willing to spend money on improving their knowledge in this area.

2 Coffee grinder from Zassenhaus

3 Cafetière from Aerolatte

4 Thermo-Cafetière from Po Selected

5 Coffee bag clip from Barista & Co.

The combination of aesthetics, craftsmanship and connoisseurship typical of the Third Wave applies equally to owners of coffee shops as to the consumers. For Horst Friedrichs, the passion with which all those involved devote themselves to coffee is of decisive importance: “These are primarily enthusiasts. And when people really enjoy a thing, something good generally comes out of it.”